The Automation Revolution

Tom Fisher, Director, Minnesota Design Center

Area of Expertise: Transportation & Urban Design

The car industry stands at the brink of an automation revolution. With an array of technologies, it's poised to transform itself from a primarily goods-producing industry, making and selling vehicles that we own and operate, to a primarily service-providing industry, offering us mobility whenever and wherever we need it. That change, already underway and likely to accelerate over the next few decades, will affect not just our transportation infrastructure—our streets, roads, and highways—but also our parking requirements and rights-of-way, our land uses, and our waterways. We cannot afford to wait for this revolution to arrive. The infrastructure investments we make today will need to accommodate the demands of a mobility services future, long before our roads and bridges, highways and parking ramps, come to the end of their useful lives.

Just as our roads had to change when we moved from horse-drawn vehicles to automobiles over a century ago, our infrastructure will likely need to change again as we move from driven cars and trucks to driverless ones.

This transformation has been a long time coming. Autonomous vehicles, for example, use radar and lidar technology common in commercial aircraft, which fly most of their routes on automatic pilot. As that well-established technology has begun to appear in ground-based vehicles, it has brought to light both pros and cons: auto-piloted automobiles could reduce the number of crashes and vehicle miles traveled, but their use may also mean reduced revenue from speeding tickets and gas taxes. The emergence of autonomous vehicles also marks a change in business strategy among car companies, as they shift from selling us automobiles every few years to providing us mobility services every day, in vehicles that they own and operate—changes that will increase their profitability while lowering our cost of travel. As these companies try to keep their cars operating at full capacity, moving passengers by day and goods at night, we will also see a dramatic reduction in the need for parking, which currently occupies, on average, 30 percent of our cities' and suburbs' land area.

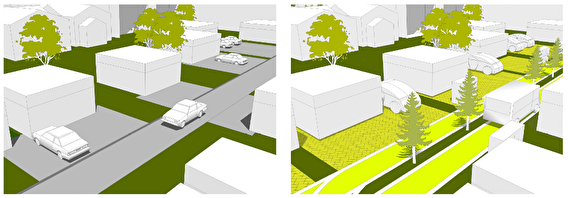

The impact of the automation revolution on infrastructure will be equally remarkable. Just as our roads had to change when we moved from horse-drawn vehicles to automobiles over a century ago, our infrastructure will likely need to change again as we move from driven cars and trucks to driverless ones. The latter follow such precise paths that they could quickly rut pavements, especially bituminous surfaces, and so will require roads to function more like railroads, using reinforced concrete tracks along the lines of travel. That will, in turn, allow roads to use fewer and narrower lanes, less pavement, and more pervious surfaces—enabling the capture of stormwater to recharge aquifers, reducing runoff into waterways, and potentially eliminating the need for storm sewers. As we make infrastructure investments, we need to start thinking now about how our current roadways can transition to these new ones.

The automation revolution will affect transportation demand as well. Trends such as the shift to hybrid work, which influences the number of people commuting and the timing of their travel; the growth of e-commerce, which enables the on-demand delivery of goods and impacts the number of vehicle miles traveled; and the rise of a sharing economy, which uses apps to connect vehicle owners to pay-per-ride passengers, have all accelerated in recent years and seem likely to remain a permanent part of American life. These trends may also alter previous assumptions about travel demand, infrastructure capacity, and investment needs while potentially reducing the overall cost of our transportation system.