There is agreement in the transportation community that the way we pay for roads needs to change.

“The motor fuel tax has been the primary source of highway revenue since the 1920s and it has served us well over the years,” says Ken Buckeye, program manager with the Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) Office of Financial Management. “However, with the advent of new sources of energy and the increase in fuel efficiency that is now federally mandated, the motor fuel tax alone is not likely to be adequate in the future. These trends are making it clear that we must begin to chart a path toward a fair and rational mileage-based fee system if we are going to meet our future needs.”

In a report sponsored by MnDOT and the Minnesota Local Road Research Board, U of M experts examined the options for implementing user-based road fees and explore the future of road pricing in the United States. Options include mileage-based user fees, toll roads and bridges, truck-only toll lanes, high-occupancy vehicle lanes, and cordon-based toll areas.

Today, user fees are not the primary source of roadway funds nationally. This is especially true for local roads, which rely primarily on property taxes. Using general-revenue sources spreads costs across non-users as well as users and sends no signal about the appropriate amount of roadway that should be built or how scarce road space should be allocated.

“While the gas tax is better than the alternative of general revenue, or not paying for roads at all, it has several problems,” says David Levinson, a professor in the Department of Civil, Environmental, and Geo- Engineering (CEGE) and the principal investigator of the study. “It does not account for inflation and rising fuel efficiency and does not apply to vehicles that do not use gasoline. It doesn’t pay for the full cost of building and maintaining local roads, recover the full costs of pavement damage from heavy vehicles, or address roadway congestion. Nor does it account for the full social costs of air pollution and crashes.”

Among all the available options analyzed, mileage-based user fees are what Levinson believes to be “the seemingly inevitable end-state for pricing and funding of roads.” Eventually, mileage charges could be used instead of a gas tax to establish a much stronger user-fee principle by charging each vehicle by miles traveled, time of day, and the type and weight of a vehicle. This is especially relevant with widespread adoption of electric vehicles and alternative fuels, he says.

Using user fees rather than general tax revenue to support roads would roughly double the out-of-pocket cost of travel by car, Levinson says. However, other costs such as property taxes, health expenses, insurance, and congestion-related time loss would decline. “Depending on its implementation, pricing presents the opportunity to fully move roads off of general revenue and internalize congestion and possibly air pollution externalities,” he says.

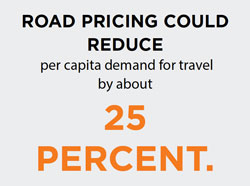

The price increase for users would have a number of implications, such as reducing per-capita demand for travel (by about 25 percent), reducing peak demand for roads, spurring denser land-use development, increasing demand for non-auto modes and carpooling, substituting delivery for shopping, and increasing telecommuting.

“Unless there’s a sudden collapse of the feasibility of the gas tax for revenue,” Levinson notes, “this will be a slow transition. We anticipate years of pricing trials and policy discussions before pricing becomes mainstream.”

Levinson’s research is part of a multi-pronged study that analyzed the technological shifts altering surface transportation and the implications for Minnesota. Other contributors included CEGE assistant professor Adam Boies and Humphrey School of Public Affairs associate professors Jason Cao and Yingling Fan. Their high-level white papers are compiled in a final report: The Transportation Futures Project: Planning for Technology Change.