Over the last 20 years, Minnesota has made significant progress in reducing traffic fatalities. Progress has stalled, however, and fatalities are now increasing year-over-year—especially since the beginning of the pandemic. On May 9, the CTS Councils convened a panel of transportation experts to frame the challenges behind the numbers and discuss what the solutions could be.

Traffic gone wild

“Mayhem in Minnesota—Traffic Gone Wild” was the unflinching title of keynote speaker Mark Kinde’s talk. Kinde, manager of the Injury and Violence Prevention Section of the Minnesota Department of Health, traced the history of Minnesota’s Toward Zero Deaths program. Before its launch, “We were killing, on average, between 600 and 650 people a year on Minnesota’s roads,” he said. Through collective action, Minnesota’s death rates fell significantly—down to 361 fatalities in 2014.

“Then we get to 2020, and things went bad,” Kinde continued. The first few months of the pandemic brought a steep rise in remote work and plummeting traffic volumes, “but soon we were seeing that something’s not right,” he said. “Our overall crashes were down, but severe injuries and deaths were already in 2020 starting to escalate.”

Preliminary fatalities for 2021 now stand at 488, a 26 percent increase over 2020 (the highest one-year percentage increase since 1943–1944) and a 37 percent increase over 2019. Speed was a factor in one third of fatal crashes in 2021; citations for people speeding at 100 miles per hour or more were three times higher in 2021 than in 2018.

Over these two years, Kinde said, there was much less appetite and support for citations. “When you take off checks and balances in operating together in society…people are inclined to do what they want. People are born selfish by nature,” he said. “When we want what we want, when we want it, and we start using an engine that can go 100 mph…it’s a prescription for problems.”

Captain Matt Markham of the Columbia Heights Police Department expanded on the challenges for law enforcement. When the pandemic began, departments tried to maintain baseline service by mitigating COVID exposure. This led to a reduction in traffic enforcement—and without enforcement, “you’re going to see people violate the law,” he said. “Then we started to see those high-flyers—those people driving over 100 miles an hour.”

The killing of George Floyd and the related civil unrest compounded the challenges. “This incident diminished trust and legitimacy within the community,” Markham said. “Law enforcement can’t do their job without the cooperation of the public.” Many officers took early retirement and others didn’t feel comfortable making traffic stops. Faced with staffing shortages, he said, officers become reactive instead of proactive.

One example of the impacts: In both 2018 and 2019, 8 drivers fled from Columbia Heights police in a motor vehicle. That number rose to 24 in 2020 and 32 in 2021, Markham said.

Solutions: Infrastructure, safe systems, and technology

Three speakers offered ideas for countering these troubling trends. Will Stein, safety engineer with the Federal Highway Administration’s Minnesota Division, said significant new investment in the federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law could be leveraged to address safety. Funding in the Highway Safety Improvement Program alone will increase 34 percent. “That’ll help us get some more good infrastructure projects out on Minnesota roads,” he said.

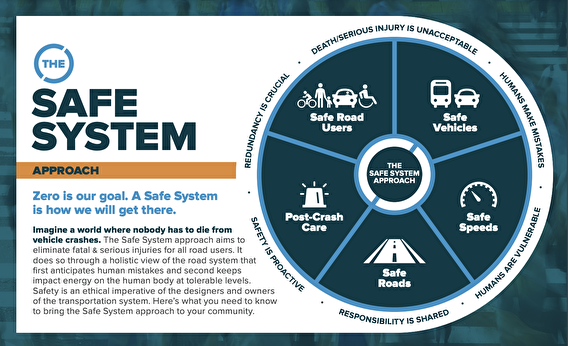

Brian Sorenson, director of MnDOT’s Office of Traffic Engineering, discussed growing interest worldwide in the Safe System approach. This holistic approach works by building and reinforcing multiple layers of protection—including safe roads, safe speeds, and post-crash care—to prevent crashes from happening and minimize harm when they do occur. A critical principle is redundancy. Humans inevitably make mistakes, he said, but the layers of protection—“like overlapping layers of Swiss cheese”—can reduce the chance of a fatality or serious injury crash finding its way through the holes.

Sorenson also emphasized the role of public acceptance and politics in traffic safety. “It is staggering to me that in our country, 40,000 deaths on our system [are] just accepted,” he declared. “A lot of times we know what the solutions are, and we have a hard time getting them implemented because the public’s not on board.”

Safe vehicles—another element of Safe Systems—are much less difficult and costly to upgrade than roadways, said Nichole Morris, director of the HumanFIRST Laboratory in the U’s Department of Mechanical Engineering. The vehicle fleet turns over about every 12 years, making safety improvements possible much faster.

“Speed limiters are a technology we have capability for today,” Morris said. “Your car can know what the speed limit of the roadway is, and there’s absolutely no reason why your car should assist you in breaking the law.” Speed limiters could also address the exponential growth in police pursuits in Minnesota and nationwide, she added.

HumanFIRST researchers are studying how to boost public acceptance of speed limiters. “If the public demanded it, original equipment manufacturers could flip a switch tomorrow and start to roll out this technology,” Morris said. Automated warnings—similar to today’s seatbelt alerts—could be an alternative.

Morris also criticized the limited rollout of automated emergency braking systems. Vehicle manufacturers had committed to making these systems widespread by 2022, but only about 60 percent offer them—mainly on more expensive models. “We could have shrunk our fatal crash rates by 30 percent if we would have gotten automated emergency braking standard,” she said. “We’ve got a huge equity issue—you have to have the means to buy safety.”

As vehicle automation becomes more common, control of most lateral and longitudinal movements will shift to the vehicle. This could prompt questions about manufacturers’ responsibility for reckless driving, she said.

Reinforcing previous speakers, Morris called for a multidisciplinary approach encompassing engineering, education, and enforcement. “You have a very weak lever when you try to pull on any one of these things in isolation.”

The webinar was sponsored by the four CTS Research Councils and the CTS Education and Engagement Council.