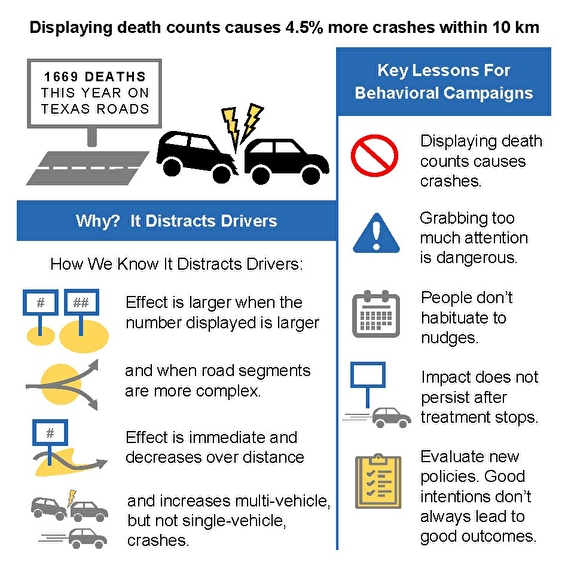

Displaying the highway death toll on message boards is a common awareness campaign, but new research from the University of Toronto and University of Minnesota indicates this tactic may actually lead to more crashes.

A new study in Science by University of Toronto Assistant Professor Jonathan D. Hall and U of M Carlson School of Management Assistant Professor Joshua Madsen evaluated the effect of displaying crash death totals on highway message boards (e.g., “1669 deaths this year on Texas roads”). Versions of highway fatality messages have been displayed in at least 27 US states.

Their study focused on Texas, where officials chose to display these messages only one week each month. The researchers compared crash data from before the campaign (Jan. 2010 – July 2012) to after it started (Aug. 2012 – Dec. 2017) and examined the weekly differences within each month during the campaign. They found:

- More crashes occurred during the week with fatality messaging compared to weeks without.

- Displaying a fatality message increased the number of crashes over the 6.21 miles following the message boards by 4.5 percent. This increase is comparable to raising the speed limit 3 to 5 mph or reducing highway troopers by 6to 14 percent, according to previous research.

- Fatality messages may cause an additional 2,600 crashes and 16 deaths per year in Texas, costing $377 million each year.

- This “in-your-face” messaging approach weighs down drivers’ “cognitive loads,” temporarily impacting their ability to respond to changes in traffic conditions.

“Driving on a busy highway and having to navigate lane changes is more cognitively demanding than driving down a straight stretch of empty highway,” Madsen says. “People have limited attention. When a driver’s cognitive load is already maxed out, adding on an attention-grabbing, sobering reminder of highway deaths can become a dangerous distraction.”

The researchers found the bigger the number in the fatality message, the more harmful the effects. The number of additional crashes each month increased as the death toll rose throughout the year, with the most additional crashes occurring in January when the message stated the annual total. They also found that crashes increased in areas where drivers experienced higher cognitive loads, such as in heavy traffic or driving past multiple message boards.

The messages also increased the number of multi-vehicle crashes but not single-vehicle crashes. “This is in line with drivers with increased cognitive loads making smaller errors due to distraction—like drifting out of a lane—rather than driving off the road,” Hall says.

However, the researchers found a reduction in crashes when the displayed death tolls were low and when the message appeared where the highways were less complex. Madsen says this suggests that at times the messaging was not as taxing on drivers’ attention.

While the use of highway fatality messaging varies by state, Madsen says agencies should consider alternative ways to raise awareness.

“Distracted driving is dangerous driving,” Madsen says. “Perhaps these campaigns can be reimagined to reach drivers in a safer way, such as when they are stopped at an intersection, so that their attention while driving remains focused on the roads.”

This research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program.

Adapted from a University of Minnesota press release.