In 2012 the Minnesota legislature modified a law—often called the Dimler Amendment—that exempts certain speeding violations from a motorist’s driving record. The modifications increased the qualifying range for the exemption from 5 mph to 10 mph in 60-mph speed zones during a roughly two-year test period that ended in the summer of 2014.

The legislation also requested a joint report from the Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) and the Department of Public Safety to learn the impacts of the modifications in terms of safety, travel reliability and efficiency, and data privacy. The U of M’s State and Local Policy Program (SLPP) at the Humphrey School of Public Affairs provided policy and data analyses for this report.

The research team, led by SLPP associate director Frank Douma, found that the impacts of the 2012 modifications were small, or even negligible. There was no consistent increase or decrease in the proportion of drivers who exceeded the speed limit, and no significant change in speed-related crash rates. “More significantly, however, our findings led us to question the effectiveness of the Dimler amendment itself,” he says.

One concern relates to the Dimler amendment’s scope and coverage. Since its passage in 1986, the law has been amended to apply to a substantially limited portion of the state’s roads—9,000 total miles. “This limited scope can create confusion regarding how the law is applied and enforced, and therefore limit its effectiveness and perceived fairness,” Douma says.

In addition, the Dimler amendment offers negligible protection for drivers’ personal information. Data vendors are still allowed to access driving records for several reasons (including resale to insurance companies), and conviction records are publicly available through the State Courts record system.

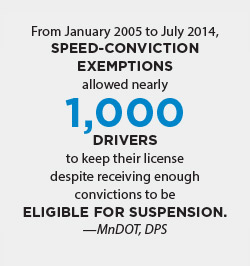

One impact the Dimler amendment does have, however, is to allow habitual speeders to stay on the road. Minnesota law states that a person’s license can be suspended for 30 days if the person is convicted of four traffic offenses within a 12-month period or five traffic offenses in a 24-month period. “Since Dimler prevents some of these convictions from appearing on a driver’s record, certain drivers are able to violate repeatedly without risking suspension,” Douma says. “This loophole is detrimental to public safety.”

The amendment also allows habitual offenders to remain eligible to apply for a commercial driver’s license. If the statute remains in effect, Minnesota may become out of compliance with new federal regulations for commercial vehicle learner permits that take effect in July 2015, he says. This would place Minnesota at risk of having up to 5 percent of federal-aid highway funds withheld.

Also because of the amendment, Douma says, habitual offenders may avoid paying higher insurance premiums that accurately reflect the public impact of their behavior—costs that are instead passed on to all other drivers in the form of higher insurance rates.

“The analyses and corresponding report provided by Frank and his team were pivotal to fulfilling the legislative requirement,” says Katie Fleming, senior research analyst with MnDOT’s Office of Traffic, Safety and Technology.