The potential of telecommuting to alter travel patterns—and even mitigate congestion during peak hours—has sparked interest among transportation planners. Despite this potential, however, the actual impact of telecommuting on traffic has remained an open question.

“In practice, the relationships between telecommuting and travel behavior vary,” says Jason Cao, an associate professor with the Humphrey School of Public Affairs. “For example, an individual might replace a commute trip by working at home but make another non-work trip because of the time savings from not making the commute trip.”

In a recent study, U of M researchers examined the impacts of telecommuting on travel behavior in the Twin Cities metropolitan area. One key finding: regular, non-daily telecommuting is on the rise. While those who telecommuted every day dropped, the number of people who telecommuted once a week or more increased, Cao says.

The research team’s first task was investigating how telecommuters and non-telecommuters differ from each other in terms of demographic and land-use characteristics. To explore the impact of telecommuting on other household members, the team divided the data into one-worker households and multiple-worker households. Some sample findings:

- In one-worker households, telecommuters tended to be more affluent, more highly educated, older, and more likely to have multiple jobs than non-telecommuters.

- Multiple-worker telecommuting households tended to be more affluent, have more members, and live in more job-rich areas than non-telecommuting households.

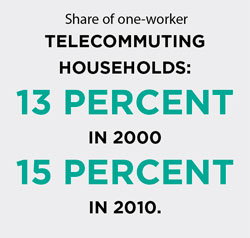

Next, researchers set out to determine how telecommuting replaces or complements auto use. Their data analysis shows that the effects of telecommuting on travel are limited for multiple-worker households, but that it tends to increase travel of one-worker households, particularly for non-work travel. The team also found that the share of one-worker telecommuting households increased from 13 percent in 2000 to 15 percent in 2010, and other telecommuting frequency categories also increased, Cao says.

Finally, researchers examined how telecommuting affects where people choose to live. Research results indicate that while telecommuting has no influence on commute distance for one-worker households, it tends to decrease average commute distances for multiple-worker households. “This suggests that the ability of one worker to telecommute may motivate the household to seek a location closer to the workplace of other household members and reduce the average commute distance,” Cao says.

“This research has revealed the complexity of telecommuting patterns and the real differences in travel between occasional, regular, and daily telecommuters,” says Jonathan Ehrlich, planning analyst with the Metropolitan Council. “We need to be aware in planning how Internet and mobile technology both replace some and necessitate other travel.”

This research is part of a five-part report sponsored by the Metropolitan Council and the Minnesota Department of Transportation based on data produced by the council’s Travel Behavior Inventory household travel survey.

Additional components of the report examine how changing accessibility of destinations has affected travel behavior, changes in walking and biking, the effect of transit quality of service on people’s activity choices and time allocation, and transportation system changes.