Minnesota is the fourth-largest producer of biofuel in the country and home to a growing livestock industry. These market forces, along with changes in the grain supply chain, are directly influencing the way grain producers and wholesalers navigate their local freight networks. To better understand these changes and their impacts, researchers in the Humphrey School of Public Affairs have collected data and developed new spatial analysis tools, ultimately aimed at informing freight transportation policy and infrastructure investment decisions.

“Ensuring efficient grain freight movement is not only necessary for the livelihoods of Minnesotans who work in the agricultural sector, it’s also crucial to the state’s economy,” says Travis Fried, a Humphrey School graduate research assistant and Master of GIS student. His work is part of research funded under the U’s Transportation and Economic Competitiveness (TPEC) Program; TPEC director Lee Munnich and researcher Tom Horan are the lead investigators.

Traditionally, trucking moves cereal grain—especially corn—to domestic market sites, Fried says. These sites include smaller country elevators, feedlots, and ethanol plants. Rail and Mississippi River barges are primarily responsible for moving bulk grain products to ports on the coast. But changes in the market for grain mean more grain is staying within Minnesota’s borders.

Ethanol in particular has rapidly transformed the corn market and supply chain, Fried says. “Last year refineries processed 5.54 billion bushels of corn—roughly a third of the state’s total corn supply. While newer plants are being equipped with rail-serving capabilities, most refineries rely on steady shipments of corn feedstock carried via truck.”

Larger feed lots and farm acreages also point to continued growth in grain production and truck traffic. “Expanding dairy farm operations in southern Minnesota have the potential to greatly impact grain feed flow, adding to the wear-and-tear of rural roads and major highway connectors,” he says.

At the same time, federal deregulation policies have given large railroad companies greater freedom to consolidate less-profitable short lines and adjust rate incentives. As a result, Fried says, large grain elevators served by major rail companies—referred to as ”shuttle elevators” for their ability to quickly load 100- to 150-car trains (shuttles) at a time—now often out-compete smaller country elevators and short lines. This effect has producers upping truck fleets and bypassing local elevators in favor of larger, more distant consolidation points.

Overall, Fried says, “today’s evolving grain supply chain has roads progressively assuming a larger responsibility for connecting farmers to the marketplace.”

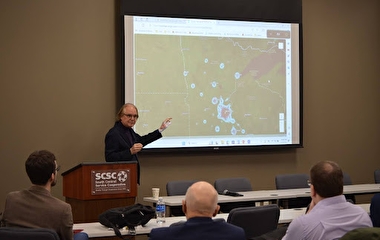

For this reason, the research team modeled grain flow patterns across key trucking corridors and shifting supply chain conditions. One of the challenges was the lack of freight data availability. “A large part of the study involved exploring different proprietary and publicly available datasets that can be used to create a more complete picture of grain commodity flow across Minnesota roads,” Fried says. In addition, the team interviewed local grain producers and freight operators.

Fried also built an original computational model that simulates local corn movements. Using the new algorithm, the TPEC team approximated corn production sites in two counties and modeled how each shipment volume of corn moves along the road network given competitive pricing of nearby markets. “Our model captures fine-tuned grain movement and shows how producers assess contracts and trucking options to determine their most profitable markets,” Fried says.

“This is exceptional work,” says Bruce Abbe, president & CEO of the Midwest Shippers Association. “It is really good to get data, especially at the local level. Minnesota’s ag transportation supply chains, particularly for corn and grain products that are exported worldwide, are continually changing in response to global market forces—and often dramatically so—due to trade disruptions. Minnesota needs to maintain and strengthen the efficiency of its diverse ag shipping infrastructure—highway trucking, bulk and container rail, river barge, and Great Lakes options. Ag shippers need to be nimble in these evolving markets.”

The TPEC team created an interactive story map—titled Amber Roads of Grain—that walks users through the study and its findings. The map is available on the TPEC website.