A typical car sits unused for more than 95 percent of its service life. Cars are just one of many things—from meeting space to power tools—that are privately owned but barely used.

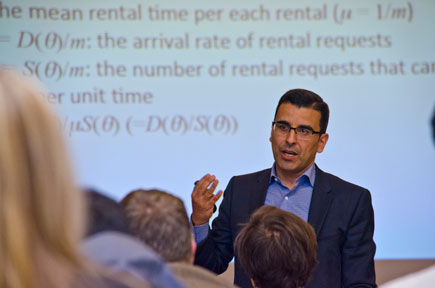

Unlocking this excess capacity is the essential idea of the sharing economy, said Professor Saif Benjaafar, director of the U of M’s Initiative on the Sharing Economy and chair of the Symposium on the Sharing Economy, held last month in Minneapolis.

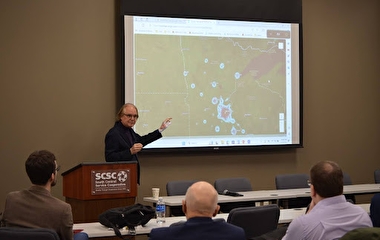

The two-day symposium was organized by the initiative and sponsored by CTS and the Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering at the University of Minnesota. It consisted of a research workshop (see related article) and a public forum.

Benjaafar set the stage for the forum with a broad picture of the issues. “The sharing economy is a growing trend away from the exclusive ownership and consumption of resources to one of shared use and consumption,” he said. “It’s greatly facilitated by online platforms such as Uber and Airbnb that reduce search and transaction costs, handle payment, and weed out bad actors.”

The sharing economy is also part of a phenomenon in which firms are shifting from selling things to selling the functionality of these things—mobility instead of cars, or power instead of engines. Ford, for example, recently launched a smartphone app that helps users find parking or share vehicles. “The pilot car-sharing program allows owners of Ford-financed cars to rent them out and put the income toward their car payments,” he said.

Many other firms and people see the promise of the sharing economy. The explosion of online platforms—Uber, Lyft, Airbnb, JustPark, LiquidSpace—in the past few years points to growing opportunities for business innovation and entrepreneurship. Individuals can earn flexible income from underused assets, and consumers can gain access to expensive things they may otherwise prefer not to own. Advocates also believe the sharing economy will improve sustainability by reducing the numbers of cars and parking spaces and lowering emissions and congestion.

But there’s also a potential dark side. “There are mounting concerns the sharing economy could lead to more consumption rather than less,” Benjaafar said, citing his recent research indicating that peer-to-peer sharing can lead to lower—or higher—ownership and usage, depending on the product’s cost. “People on the cusp of buying something expensive may make the purchase if they can rely on rental income as a subsidy,” he said.

Some forecasts predict higher vehicle-miles traveled due in part to the young and old having greater accessibility. And New York City officials are questioning if the rise of Uber and other app-based car-sharing services—and the resulting cars circling streets and making stops—caused a 9 percent decrease in average speeds in the city center between 2010 and 2014.

Other concerns are that the sharing economy competes unfairly against existing businesses, such as regulated cab companies, and leads to a “gig” economy that puts downward pressure on wages and shifts corporate risk to individuals.

So what are the actual perils and promise? “Things may not go according to what advocates on either side tell us,” Benjaafar said. “Our initiative will provide objective analysis.” The growing team includes researchers from multiple U of M departments plus partners at the Singapore University of Technology and Design.

Following his remarks, the forum turned to presentations and panels with leaders from industry (including Nice Ride, HOURCAR, and Zipcar), academia, nonprofits, and government. Video recordings of the event are available on the Initiative on the Sharing Economy website. A summary report will also be available.